This is a specific subject page, dealing exclusively with, or primarily with, the subject in the title. Because of need, there are many such pages at RHWW: usually, but not always, linked to primary pages. For those in a hurry, they enable a quick summary of many important subjects. The menu for these pages is here: Click>>>

Black U.S. Indians and Paleoamericans

Paleoamerican is a classification term given to the first peoples who entered, and subsequently inhabited, the American continents during the final glacial episodes of the late Pleistocene period. They are known to be Black Polynesians and Australoids: but since those people are genetically and by remains phenotype, indistinguishable from the Black people still in Africa, it makes Africa a possible "Direct" source of Paleoamericans, perhaps the most likely, as it is much closer.

Why Christopher Columbus called them INDIANS!

|

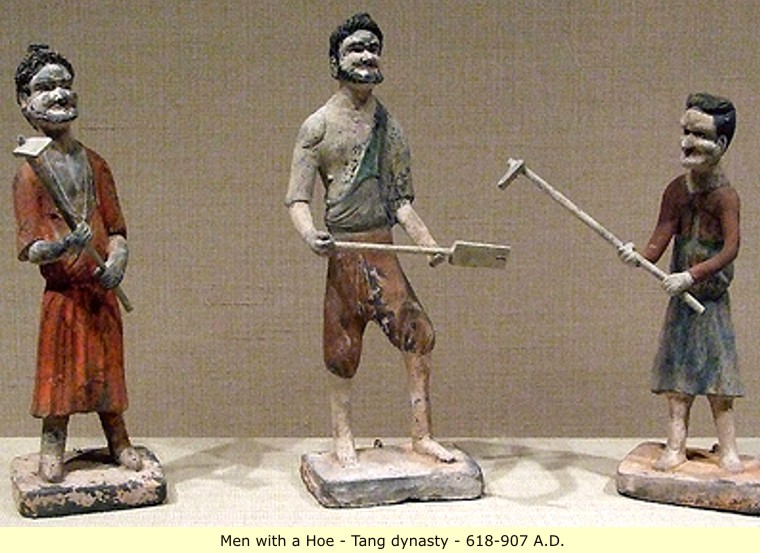

Those people termed "Native Americans" are "Later" Asian migrants to the Americas. This group would include East Asian Blacks, such as the ancient Shang and jomon. But perhaps most numerously, the Mongol type people, and incredibly: European type Albinos! For let us not forget that the European Albino is in fact a "Central Asian", and they were known to wonder all over Asia before migrating "In-mass" to Europe. Ancient Chinese artifacts depicting European Albino type people (Caucasians), clearly attests to their presence in Eastern China. So it should come as no surprise that they "MIGHT" have crossed the Bering Straits and entered the Americas, along with the Asian Blacks and Mongol type people.

|

It is also indisputable that all of "North Americas - Native Americans" are Mulattoes and Whites. It is possible that "SOME" are "ANCIENTLY" derived from European Albino/Mongol and Black stock! Though it can not be gauged how much mixing occurred between the very first Europeans in the Americas (the Frontiersmen), and the Native Americans. However, resent research indicates that the admixture from frontiersmen was extensive, as new artifacts demonstrate that "Pure" Indians were Blacker than first thought.

United States National Park Service

(self-proclaimed: one of the United States' leading agencies for history and culture).

African Nation Founders

Africans in the Low Country

Work, Marriage, Christianity

Many of these early slaves were American Indians, mostly Algonquian-speakers of coastal Virginia and North Carolina. By the 1680s, English settlers routinely kidnapped Native American women and children in the coastal plains of North Carolina and Virginia. This Native American slave trade involved a number of colonies, including Virginia, Carolina, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Jamaica, Barbados, St. Kitts, and Nevis. So many Indian slaves were traded to Pennsylvania that a law was passed in 1705 forbidding the importation of Carolina Indian slaves. This was done in part because many of the slaves were Tuscarora who were aligned militarily with the Iroquois Confederacy, which threatened to intervene to stop the trade.

From 1680 to 1715, the English sold thousands of Indians into slavery, some as far away as the Caribbean. Indian slavery, however, had many problems, not the least of which were Indian attacks, and by 1720, most colonies in North America had abandoned it for African slavery. In 1670, Virginia passed a law defining slavery as a lifelong inheritable “racial” status. After the passage of this law many “black Indians” found themselves classified as black and forced into slavery.

In the fields and homes of colonial plantations, mutually enslaved African Americans and American Indians forged their first intimate relations. In spite of a later tendency in the Southern colonies to differentiate the African slave from the Indian, chattel slavery was built on a preexisting system of Indian slavery.

Even though the arrival of Africans in 1619 began to change the face of slavery in North America from “tawny” Indian to “blackamoor” African, Indian slaves were exported throughout the Caribbean often in trade for Africans. As the 18th century dawned the slave trade in American Indians was so serious that it eclipsed the trade for furs and skins and had become the primary source of commerce between the English and the South Carolina colonials (Minges 2002:454).

During this transitional period, Africans and Americans Indians shared the common experience of enslavement. They worked together, lived together in communal quarters, produced collective recipes for food, shared herbal remedies, myths and legends and in the end they intermarried. Africans had a disproportionate numbers of males in their population while Native American women and children were disproportionately enslaved. American Indians males were shipped to the Caribbean, died in wars or of European diseases. As traditional societies in the Southeast were primarily matrilineal, African males who married American Indians women often became members of the wife’s clan and of her nation

The 1740 slave codes of South Carolina served to blur the distinction between African, American Indian and the children of their intermarriage, declaring: All negroes and Indians, (free Indians in amity with this government, and negroes, mulattoes, and mustezoses, who are now free, excepted) mullatoes and mustezoes who are now, or shall hereafter be in this province, and all their issue and offspring…shall be and they are hereby declared to be, and remain hereafter absolute slaves (Hurd 1862:303 as cited in Minges 2002:455)

https://www.nps.gov/ethnography/aah/aaheritage/lowCountry_furthRdg1.htm

|

|

|

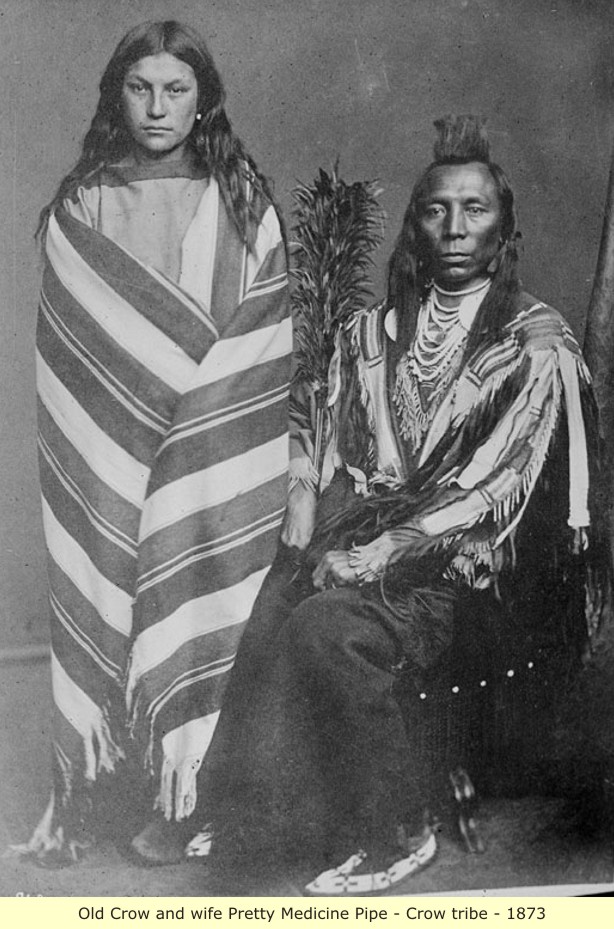

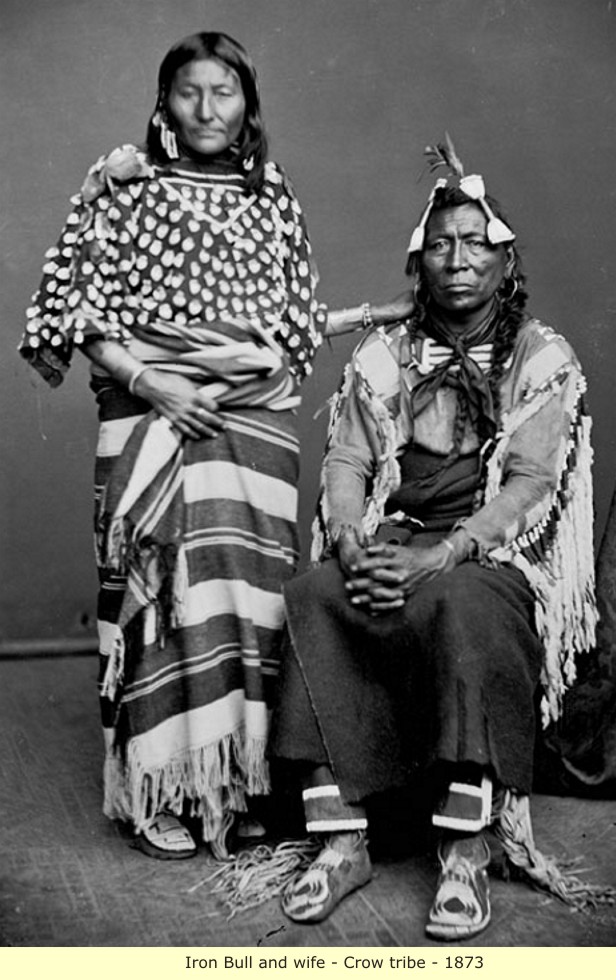

Click here for an enlargment of this photo: >>>

|

|

|

|

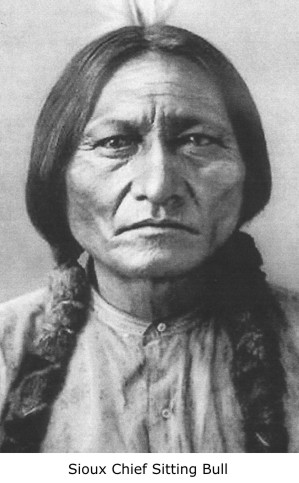

Mulatto Indians

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It wasn't only "Frontiersmen"

it was also Frontierswomen causing admixture.

|

|

However, an enduring mystery is why "Pure" Mongol type people, mostly appear in Central and South America, despite the fact that they obviously entered the Americas by way of the Bering Straits.

|

|

|

|

|

|

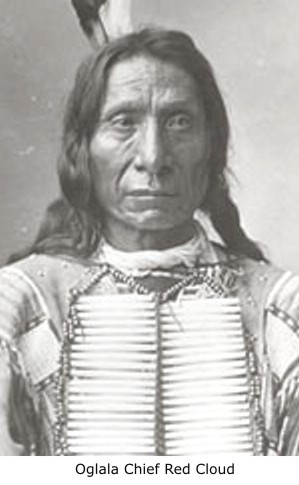

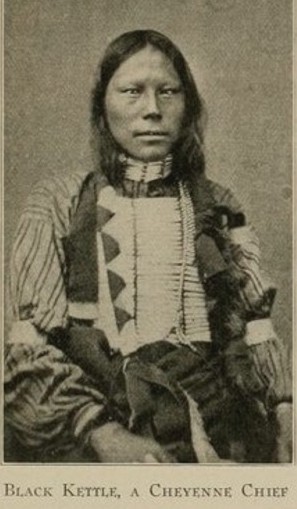

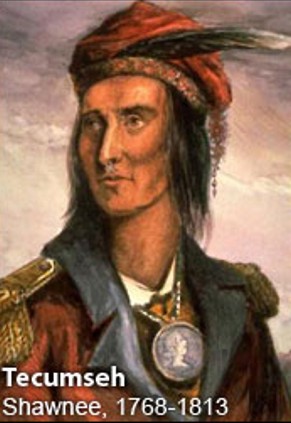

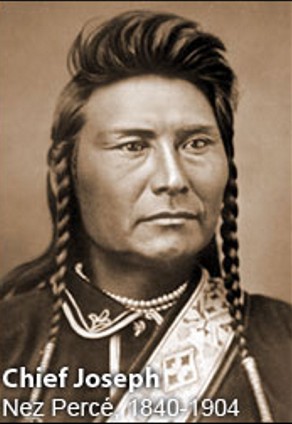

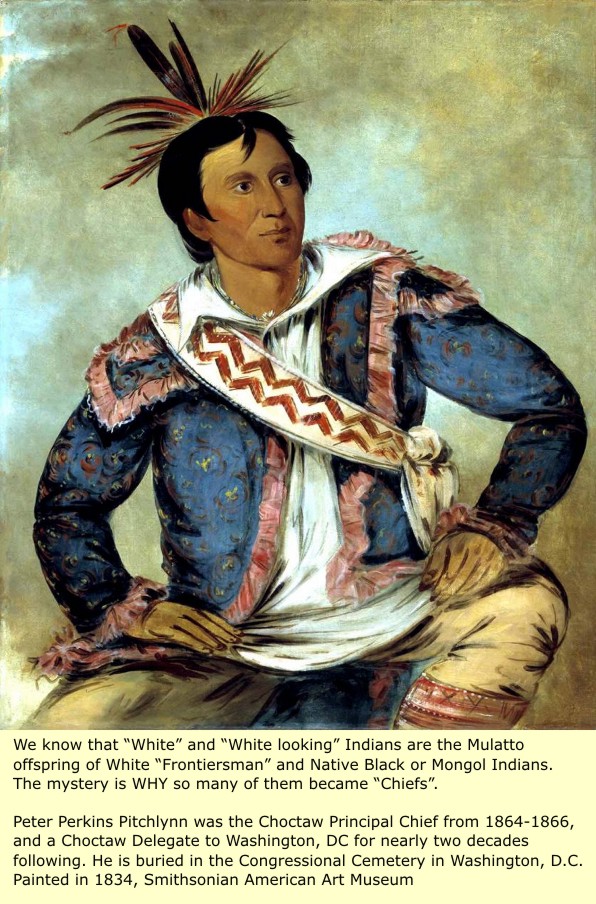

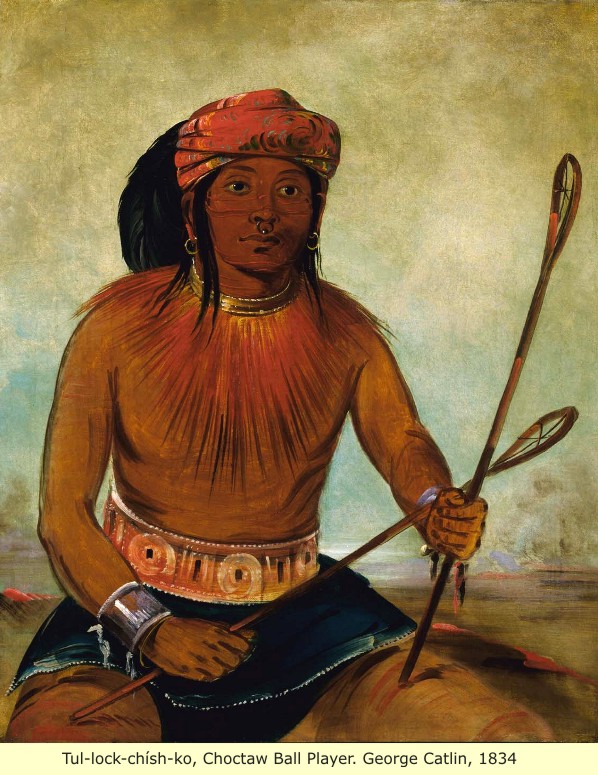

We know that “White” and “White looking” Indians are the Mulatto offspring of White “Frontiersman” and Native Black or Mongol Indians. The mystery is WHY so many of them became “Chiefs”.

|

|

|

|

|

|

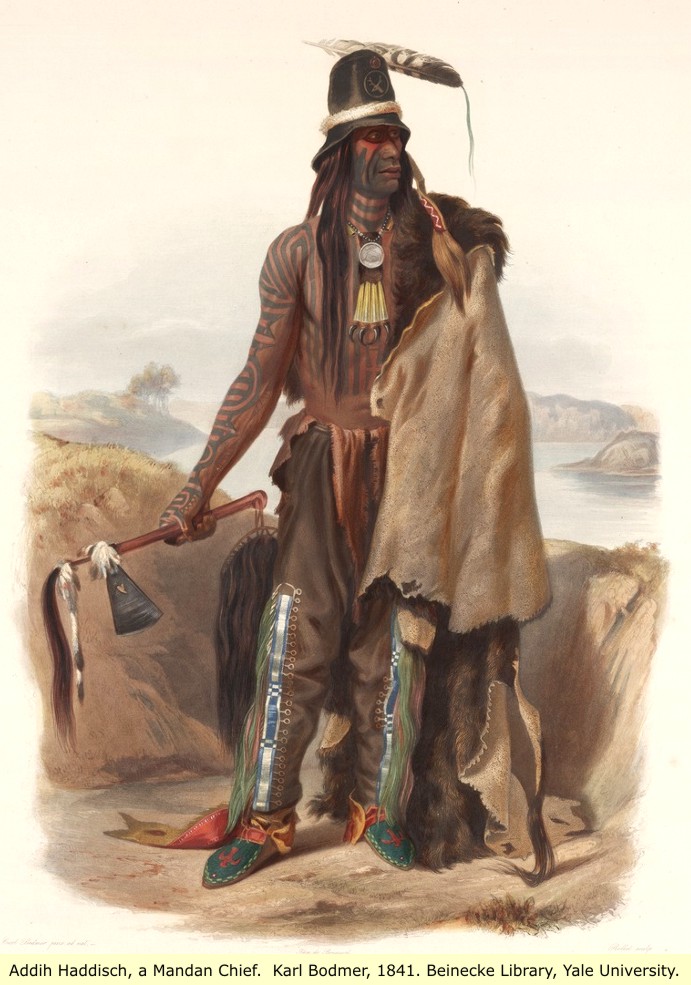

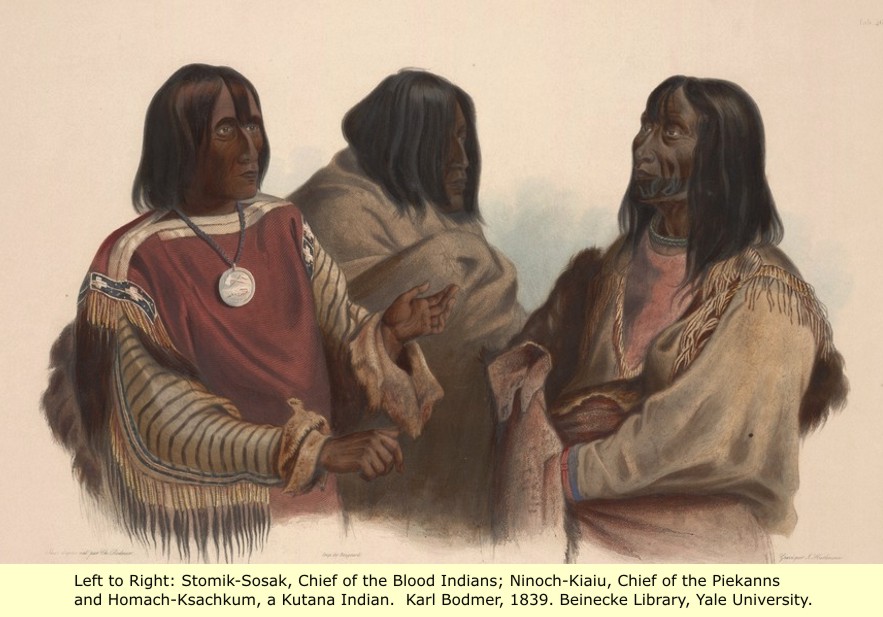

An interesting note:

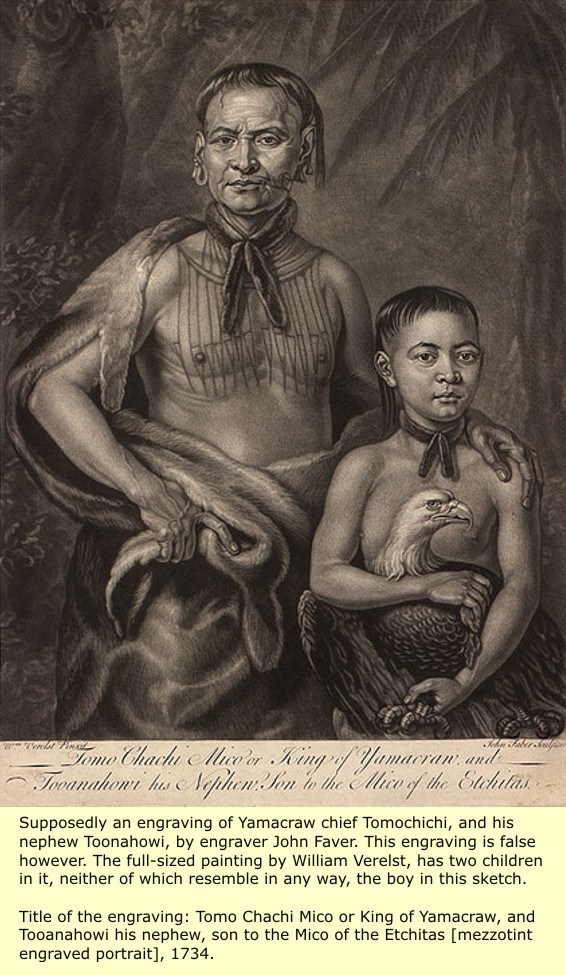

Judging by these two mezzotint etchings, the British public though the Black native American tribes,

more emblematic of the Americas than the Mongol/mix mulatto tribes.

|

|

Blood quantum laws

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws, is legislation enacted in the United States to define membership in Native American tribes or nations. "Blood quantum" refers to describing the degree of ancestry for an individual of a specific racial or ethnic group, for instance: 1/2 by the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (equivalent to one parent), 1/4 by the Hopi Tribe of Arizona (equivalent to one grandparent), 1/8 by the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma (equivalent to one great-grandparent), 1/16 by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina (equivalent to one great-great-grandparent), 1/32 by the Kaw Nation (equivalent to one great-great-great-grandparent).

Its use started in 1705 when Virginia adopted laws that limited colonial civil rights of Native Americans and persons of half or more Native American ancestry. The concept of blood quantum was not widely applied until the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The government used it to establish the individuals who could be recognized as Native American and be eligible for financial and other benefits under treaties that were made or sales of land.

Since that time, however, Native American nations have established their own rules for tribal membership, which vary among them. In some cases, individuals may qualify as tribal members, but not as American Indian for the purposes of certain federal benefits, which are still related to blood quantum. In the early 21st century some tribes have tightened their membership rules and excluded people who had previously been considered members, such as in the case of the Cherokee Freedmen.

The Cherokee Freedmen Controversy is an ongoing political and tribal dispute between the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen regarding tribal citizenship. During the American Civil War, the Cherokee who supported the Union abolished the practice of African slavery by act of the Cherokee National Council in 1863. The Cherokee Freedmen became citizens of the Cherokee Nation in accordance with a treaty made with the United States government a year after the Civil War ended. In the early 1980s, the Cherokee Nation administration amended citizenship rules to require direct descent from an ancestor listed as "Cherokee by Blood" on the Dawes Rolls. The change stripped descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen of citizenship and voting rights unless they satisfied this new criterion. About 25,000 Freedmen were excluded from the tribe.

Cherokee freedmen

On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Supreme Court ruled that the descendants of the Cherokee Freedmen were unconstitutionally kept from enrolling as citizens and were allowed to enroll in the Cherokee Nation. Chad "Corntassel" Smith, then-Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, called for an emergency election to amend the constitution in response to the ruling. After a petition was circulated, a special election held on March 3, 2007 resulted in a constitutional amendment that disenrolled the Cherokee Freedmen descendants. This led to several legal proceedings in United States and Cherokee Nation courts in which the Freedmen descendants continued to press for their treaty rights and recognition as Cherokee Nation members. The 2007 constitutional amendment was voided in Cherokee Nation district court on January 14, 2011, but was overturned by a 4-1 ruling in Cherokee Nation Supreme Court on August 22, 2011, before the special run-off election for Principal Chief. The ruling excluded the Cherokee Freedmen descendants from voting in the special election.

After the freezing of $33 million in funds by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and a letter from the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in response to the ruling, an agreement in federal court between the Cherokee Nation, the Freedmen descendants and the US government allowed the Freedmen to vote in the special election. Bill John Baker was elected Principal Chief in the special election and inaugurated in October 2011. The Cherokee Supreme Court dismissed an appeal of the election results by former chief Chad Smith. Both sides filed complaints in federal court in Tulsa, Oklahoma, by July 2012; the Cherokee say the 1866 treaty does not require them to give full citizenship to the Freedmen, who continue to seek full rights. The first hearing on the merits of the case was held in May, 2014 in the U.S. District in Washington, D.C.

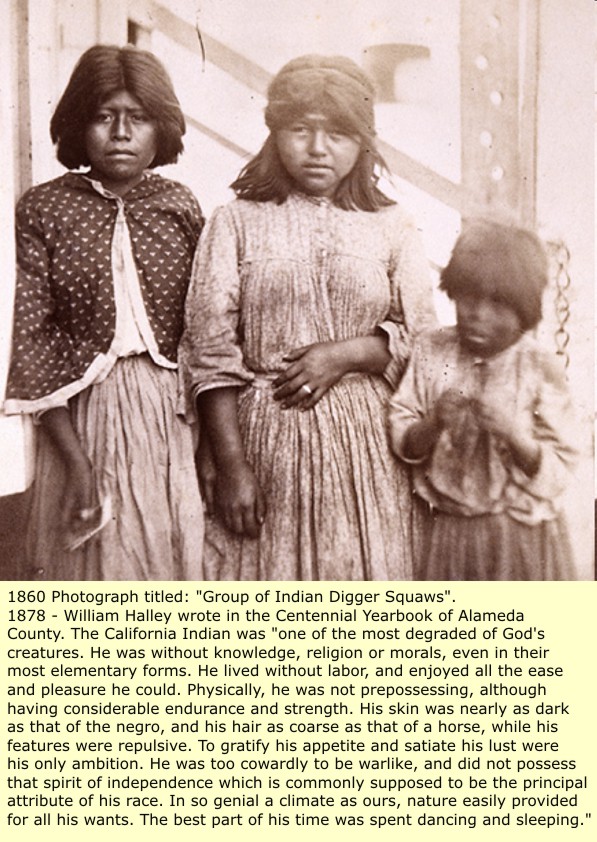

California Indians

The state of California was home to more than 100 tribes of Paleoamericans (Black tribes) and Native Americans (Mongol extraction).

The Ohlone people

Ohlone people, also known as the Costanoan, are a Native American people of the central and northern California coast. When Spanish explorers and missionaries arrived in the late 18th century, the Ohlone inhabited the area along the coast from San Francisco Bay through Monterey Bay to the lower Salinas Valley. At that time they spoke a variety of languages, the Ohlone languages, belonging to the Costanoan sub-family of the Utian language family, which itself belongs to the proposed Penutian language phylum. The term "Ohlone" has been used in place of "Costanoan" since the 1970s by some descendant groups and by most ethnographers, historians, and writers of popular literature. In pre-colonial times, the Ohlone lived in more than 50 distinct landholding groups, and did not view themselves as a distinct group. They lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering, in the typical ethnographic California pattern. The members of these various bands interacted freely with one another as they built friendships and marriages, traded tools and other necessities, and partook in cultural practices. The Ohlone people practiced the Kuksu religion. Before the Spanish came, the northern California region was one of the most densely populated regions north of Mexico. However in the years 1769 to 1833, the Spanish missions in California had a devastating effect on Ohlone culture. The Ohlone population declined steeply during this period.

The Ohlone living today belong to one or another of a number of geographically distinct groups, most, but not all, in their original home territory. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has members from around the San Francisco Bay Area, and is composed of descendants of the Ohlones/Costanoans from the San Jose, Santa Clara, and San Francisco missions. The Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation, consisting of descendants of intermarried Rumsen Costanoan and Esselen speakers of Mission San Carlos Borromeo, are centered at Monterey. The Amah-Mutsun Tribe are descendants of Mutsun Costanoan speakers of Mission San Juan Bautista, inland from Monterey Bay. Most members of another group of Rumsien language, descendants from Mission San Carlos, the Costanoan Rumsien Carmel Tribe of Pomona/Chino, now live in southern California. These groups, and others with smaller memberships (see groups listed under the heading Present Day below) are separately petitioning the federal government for tribal recognition.

Louis Choris

Louis Choris (1795-1828) was a famous German-Russian painter and explorer. He was one of the first sketch artists for expedition research. Louis Choris, who was a Russian of German stock, was born in Yekaterinoslav, now Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine on March 22, 1795. He visited the Pacific and the west coast of North America in 1816 on board the Ruric, being attached in the capacity of artist to the Romanzoff expedition under the command of Lieutenant Otto von Kotzebue, sent out for the purpose of exploring a northwest passage.

Choris is said to have "painted nature as he found it. The essence of his art is truth; a fresh, vigorous view of life, and an originality in portrayal." The accompanying illustrations may therefore be looked upon as faithfully representing the subjects treated by the artist. After the voyage of the Ruric, Choris went to Paris where he issued a portfolio of his drawings in lithographic reproduction and studied in the ateliers of Gerard and Regnault. Choris worked extensively in pastels. He documented the Ohlone people in the missions of San Francisco, California in 1816.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

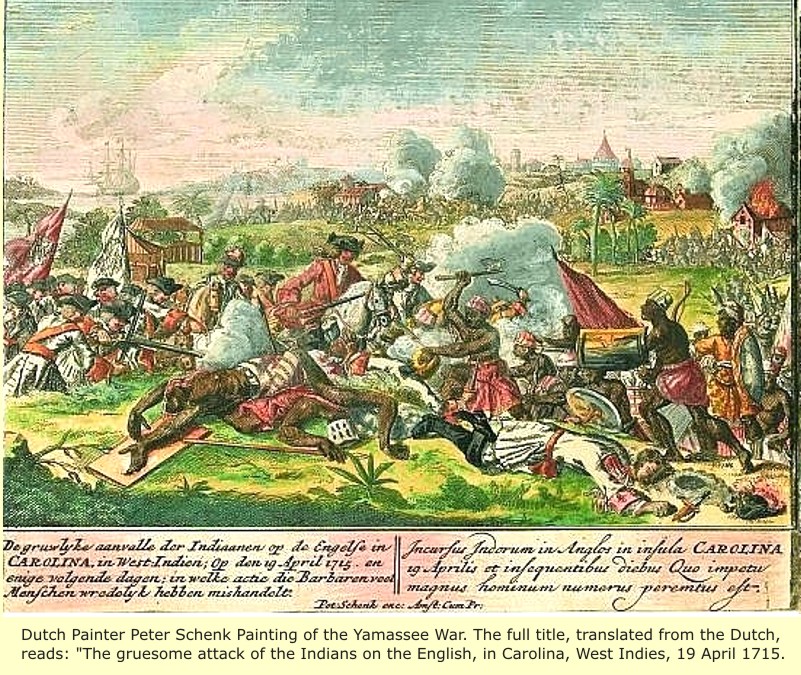

The Yamasee War

The Yamasee Indians were part of the Muskhogean language group. Their traditional homelands lay in present-day northern Florida and southern Georgia. The advent of the Spanish in the late 16th century forced the Yamasee to migrate north into what would become South Carolina. Relations between the tribe and English settlers in that region were generally positive during the latter half of the 17th century.

Not surprisingly, problems between the races developed. The continuing influx of white settlers put pressure on Indian agricultural and hunting lands. The relationship was further complicated in that the tribe had become dependent on English firearms and other manufactured items, and had incurred a large debt, typically payable in deerskins. White fur traders acted on their displeasure by enslaving a number of Yamasee women and children to cover portions of the outstanding debt.

In the spring of 1715, the Yamasee formed a confederation with other tribes and struck at the white settlements in South Carolina. Several hundred settlers were killed, homes burned and livestock slaughtered. The frontier regions were emptied; some fled to the relative safety of North Carolina and others pushed on to even more secure Virginia. Charleston also received large numbers of frightened settlers.

At the height of the fighting, it appeared that the tribal confederation's overwhelming numerical superiority would end in the white settlements' complete destruction in the region. This would have been a virtual certainty if the confederacy had successfully drawn the Cherokee into their cause. Instead, the Cherokee gave in to the lure of English weapons and other goods, and chose to aid the Carolinians. In a further stroke of good fortune, the besieged settlers also managed to gain support from Virginia ~ez_mdash~ an event not assured in this age of intense colonial rivalries.

The tide turned against the Yamasee, who were slowly pushed south through Georgia back into their ancestral lands in northern Florida. There, the tribe was virtually annihilated by protracted warfare with the Creeks, but some members were absorbed by the Seminole.

The Yamasee War took a heavy toll in South Carolina. Such terror had been instilled in the minds of the frontiersmen that it would take nearly 10 years for resettlement to occur in many areas. The warfare also brought a sharp change to the region's economy. Originally, farming had been the settlers' primary occupation, but the livestock supply had been so drastically depleted that many farms disappeared. In their absence, enterprising South Carolinians turned to the forests as a source of naval stores (tar, pitch and turpentine) and soon developed a lucrative trade with England. Later, the economy would develop rice and indigo as its primary products.

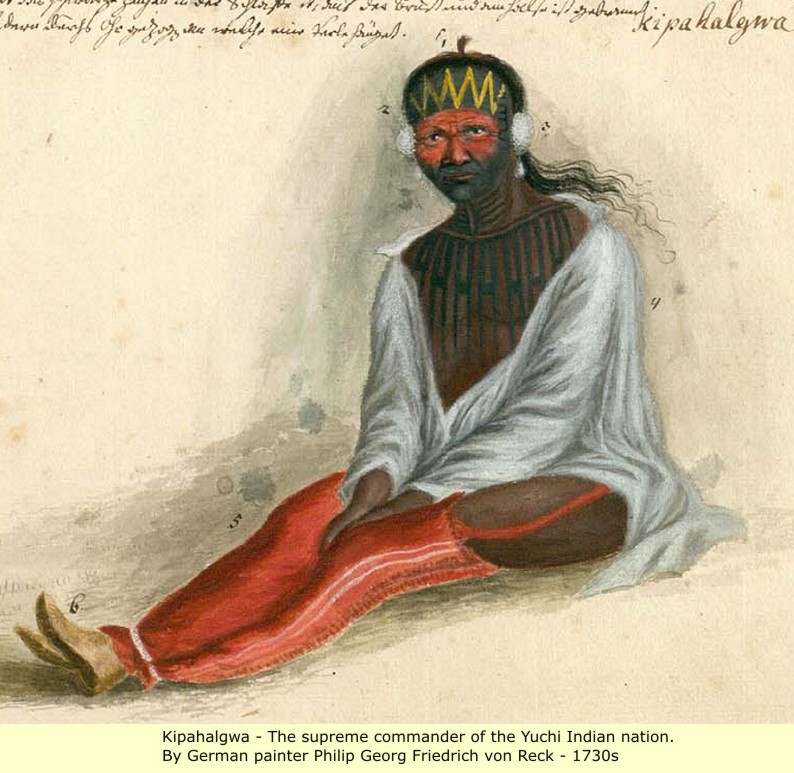

The Tsoyaha (Yuchi)

The Tsoyaha (Yuchi) are not well represented in the history books. This is for several reasons. First, while the Yuchi were a large and powerful tribe according to reports of the De Soto expedition, evidence indicates that disease epidemics ravaged the Yuchi after the Spanish men visited the East Tennessee area. The Yuchi were known to have widely scattered villages that ranged from Florida to Illinois, and from the Carolina coast to the Mississippi River. Legend has it that the tribe split in half over politics, and the fate of remaining half is not known. This actually seems to have happened several times over the past as portions of the tribe were absorbed into the Shawnee, Lenape, Cherokee and Creek peoples, as well as into the dominant culture. We do know that for at least 6 or 8 centuries much of what is now Tennessee was occupied by a tribe with cultural characteristics that like the Mouse Creek site had significant elements of the Yuchean cultural footprint. The Yuchi villages were very often intermingled with those of the neighboring tribes. It was widely theorized that the Yuchi in their widely scattered villages throughout the Southeastern United States, represented the original inhabitants prior to the influx of the Muskhogean, Iroquoian, and Algonkian Peoples. The Yuchi themselves avow that only the Algonkian (Lenape) were already here when they came -- and call them the "Old Ones" still. It is certain that the Yuchi were among the Mound-building People, and therefore among the oldest recognizable permanent residents of the Southeast United States. They held a pivotal role in this rather sophisticated society as priests, leaders and traders in what was a very metropolitan culture.

|

|

|

After suffering many fatalities due to epidemic disease and warfare in the 18th century, several surviving Yuchi were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s, together with their allies the Muscogee Creek. (Some who remained in the South were classified as "free persons of color"; others were enslaved.) Some remnant groups migrated to Florida, where they became part of the recently formed Seminole Tribe of Florida. Today the Yuchi live primarily in the northeastern Oklahoma area, where many are enrolled as citizens in the federally recognized Muscogee Creek Nation. Some Yuchi are enrolled as members of other federally recognized tribes, such as the Absentee Shawnee Tribe and the Cherokee Nation.

|

|

|

Click here for a large picture of the Yamacraw Indians in London

|

Please note: According to the book "Transatlantic Encounters: American Indians in Britain", 1500-1776 By Alden T. Vaughan: Tomochichi was NINETY YEARS OLD IN 1734! All that proves is that the Albinos do indeed make it up as they go. The question is, which, if any of it, is true? |

Examiner: British researchers probe mystery of lost Native American artifact.

It is the Rosetta Stone of North America. The English translation of this hand-painted vellum containing a lost Native American writing system, requires eight printed pages. With the encouragement of His Royal Highness, Charles, Prince of Wales, a search has begun on both sides of the Atlantic to find the original artifact, or at least a copy of the writing system. It has been misplaced for over 230 years. The year is 1733. Growing increasingly fearful of a combined Spanish, French and Indian attack on its vulnerable white population, the Province of South Carolina agreed to renounce claims on territory southwest of the Savannah River so that a new colony of yeoman farmers could be established on its frontier. Roughly sixty percent of South Carolina’s population was either African or Native American slaves. These suppressed peoples would be highly inclined to assist the French and Spanish. In 1715, without the direct assistance of European powers, the Yamasee Indians had almost succeeded in wiping the southern part Carolina off the face of the earth. Back then there was no North or South Carolina. A new alliance of tribes in the Carolina Mountains switched sides and attacked the Yamasee just at the moment when Charleston faced annihilation. This alliance was now called the Cherokees. The new colony, called Georgia in honor of King George I, would have no slaves. Its first town, Savannah, had been designed in advance as a military bastion. Its unique plan maximized the defensive effectiveness of artillery. All males in the colony agreed to be members of the militia in return for being given free land. The colony’s Board of Trustees planned to recruit the thousands of Englishmen in debtor’s prisons, plus German Protestants, being persecuted in Catholic regions, to settle the countryside. Unlike Maryland, Virginia, South and North Carolina, there would be no plantation aristocracy. At least, that was the plan. The key to this colony’s success would be good relations with the Muskogean peoples of the interior. Prior to the Yamasee War, they had been divided up into provinces of various sizes. The strongest province was itself an alliance known to the British as the Ochese Creek Indians. At about the same time in 1718 that the Mountain Alliance was given the name Cherokees, the Muskogeans formed their own regional confederacy from provinces speaking several languages and dialects. The Muskogean Confederacy was not a tribe at this time, but would eventually evolve into the Creek Indians. Nevertheless, in 1733, this alliance contained the largest and most culturally advanced indigenous population in North America. It claimed all the former lands of its members, between the Smoky Mountains in North Carolina southward to St. Augustine, FL. Expansion of the Cherokee Alliance into western North Carolina had forced many Muskogean provinces to relocate to Alabama and Georgia. Its members would not be called “the Creek Indians” until the 1740s. The founding of the Province of Georgia Savannah was settled in February of 1733 on land given to British Crown by a small Muskogean tribe, known as the Yamacraw. Its leader, Tamachichi (Tomochichi in English) had been banished from Muskogean Confederacy for some unknown incedent. About 1728 Tomochichi created the Yamacraws from an assortment of Muskogean and Yamasee Indians after the two alliances disagreed over future relations with Great Britain and Spain. This Yamacraw village would remain adjacent to Savannah until the American Revolution. Immediately, Tamachichi and Governor James Edward Oglethorpe became close friends. In November of 1733, Tamachichi invited the highest leaders of the Muskogean Confederacy to Savannah to meet his friend, James Oglethorpe. Tamachichi’s prestigious new status as a close ally of Great Britain brought him reinstatement into the confederacy. British officials were shocked to learn that the Indians in the interior were not one ethnic group, but many peoples with separate histories reaching back over 2,000 years. They were the vestiges of the mound-building era. The leaders agreed to be steadfast allies of Great Britain. The Okonee Province (Ocute in the de Soto Chronicles) agreed to give Oglethorpe all their land that he needed along the Atlantic Coast to establish a healthy colony. Governor Oglethorpe immediately sent a long letter back to British government that described their new allies, who seemed very different from any Indians that the British had dealt with before. He was astonished that they were skilled in writing, math, astronomy and land surveying without being taught these skills by Europeans. He told the prime minister that he was convinced that these new allies were the descendants an ancient civilization. The Migration Legend of the Kashita People Early in 1734 a delegation of Muskogean Confederacy leaders returned to Savannah to confirm their alliance with Oglethorpe. This delegation was lead by Chikili, the war chief of the Palache (Apalache) who formerly lived in the gold fields of the Georgia Mountains, but now lived in the region northwest of Savannah. The highlight of a friendship ceremony was the presentation of a vellum made from a bison calf skin. On this vellum was painted in the Muskogean writing system, the history of the Kas’hita People. They were late arrivals to the Southeast. As Chikili read the vellum, Indian trader, John Musgrove and his beautiful Indian wife, Kusaponakeesa, translated the legend into English, while a notary wrote down the information. The Creek Indian writing system was capable of transmitting all verb tenses and complete thoughts. The Kashita People called themselves, the Kauche-te, in their Itsate Creek language. They were originally vassals of Kusa, the great town visited by Hernando de Soto in the summer of 1540. At some time in the past, they moved northward to live among the Talasee Creeks in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, then moved to an abandoned town site on the Hiwassee River near present-day Murphy, NC. Juan Pardo visited them in the fall of 1567. He called them the Cauche. In their migration legend, the Kashita claim to have sacked a great capital on the side of Georgia’s highest mountain, Brasstown Bald. The Kashita’s description of this town seems to match the Track Rock terrace complex site. Governor Oglethorpe immediately realized the scientific importance of the Kashita vellum. He dispatched it to England for safe-keeping. It created quite a stir in England. The American Gazetteer newspaper published a full translation and described as written with peculiar red and black characters, not pictures as normally seen on American Indian skin paintings. It reportedly was mounted in a frame on the wall of the Georgia Office in Westminster Palace as long as Georgia was a colony then misplaced. See the following URL for more complete discussions of the Creek Indians’ migration legends: http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/the-migration-legend-of-the-kashita-people.htm The on-going research into the cultural connections between the Southeast and Mesoamerica has sparked a renewed interest in the long forgotten bison calf vellum. Tamachichi’s name was Itza Maya. It means “Merchant Dog.” Of particular interest is the statement in contemporary London papers that the Creek Indian’s writing system consisted of “peculiar red and black characters.” During the Terminal Classic and Post-Classic Periods, the Itza Mayas used a simplified Maya writing system consisting of red and black characters. A mineral mined in Georgia was found on the buildings at Palenque, the Classic Period capital of the Itza Mayas in Chiapas. Clarence House picks up the rugby ball The premier of American Unearthed on December 21, 2012, about the Creek Indian-Maya connection, had the highest viewership of any program ever watched on History Channel H2. It is now being viewed by people around the world. Intrigued by the research, His Royal Highness, Charles, Prince of Wales, directed one of his personal secretaries at Clarence House to assist in the search for the lost buffalo calf vellum. Clarence House is the official residence of the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall. The staff at Clarence House reported on January 28, 2013 has already turned up some previously unknown details about the lost vellum. Tamachichi and several family members were guests of the Archbishop of Canterbury when they visited England in 1734. His barge was at their disposal. In a ceremony on August 18, 1734 Tamachichi and Governor Oglethorpe formally presented the vellum to Archbishop William Wake at Lambeth Palace. The vellum has been the official property of the Church of England since then. It may be in the church archives rather than in the British Museum. In a recent conversation with the Friends of Oglethorpe Society, Clarence House official, Grahame Davies, has learned that a Lutheran minister, the Rev. Martin Boltzius, copied portions of the Creek writing system then included them in personal correspondence to Lord Edgemont in England. Boltizius was the leader of the Saltzburger Colony at New Ebenezer, GA. The next step in the research process will require the laborious study of archives held by the Church of England, British Museum, British Government and the James Oglethorpe Room at the Godalming Museum in Surrey, UK. See http://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/places/surrey/waverley/godalming/godalming_westbrook_manor/. The results of this research could again turn the world of archaeology upside down. American anthropologists have traditionally refused to label the Southeastern Indians as “civilized” because "they did not have a writing system until the early 1800s, when Sequoyah created the Cherokee Syllabary.” There will not be a whole lot that the anthropologists can say, when an official at Clarence House presents the Creek writing system to the world. |

Trustee Georgia, 1732-1752

Edward J. Cashin, Augusta State University

The first twenty years of Georgia history are referred to as Trustee Georgia because during that time a Board of Trustees governed the colony. England's King George signed a charter establishing the colony and creating its governing board on April 21, 1732. His action culminated a lengthy process.

Origins

James Edward Oglethorpe, famous for conducting a parliamentary investigation into the conditions of London prisons, exercised a leading role in the movement to found the new colony.

James Oglethorpe, a leader in the British movement to found a new colony in America, set sail for the new world on November 17, 1732, accompanied by Georgia's first settlers.

He confided to his friend John Lord Viscount Percival (known as the first earl of Egmont after that title was conferred on him in 1733) that he intended to help released debtors begin a new life in America. In fact, Oglethorpe had received a grant of £5,000 to carry out his plan. In 1729 Dr. Thomas Bray chose trustees to administer his estate. In addition to Oglethorpe, the trustees, called the Associates of Dr. Bray, included several future members of the Georgia Trust, notably Percival, James Vernon, and Thomas Coram. Coram is better known as the founder of the Foundling Hospital in London. Oglethorpe and his friends decided to add the Bray legacy to the funds in hand for the purpose of establishing a new colony between the Savannah and Altamaha rivers, in territory claimed by both the province of South Carolina and the Spanish colony of Florida.

On September 17, 1730, the associates presented a petition for a charter to the Privy Council, Parliament's executive body, headed by the chancellor of the exchequer, Robert Walpole. The petition was routinely passed on to the notoriously inefficient Board of Trade, which dawdled for a year without acting. Walpole, the prime minister, was less than eager to challenge the Spanish, who had a prior claim to the region requested by the petitioners. Walpole needed the support of the influential members of Parliament who supported the charter, however, and he managed to bring the charter before the Privy Council. After going through several revisions, the notion of helping debtors gave way to a more pragmatic plan to send over "the deserving poor" who would protect South Carolina while producing such goods as wine and silk for England.

The colonists were entitled to all the rights of Englishmen, yet there was no provision for the essential right of local government. Religious liberty was guaranteed, except for Roman Catholicism and Judaism. A group of Jews landed in Georgia without explicit permission in 1733 but were allowed to remain. The charter created a corporate body called a Trust and provided for an unspecified number of Trustees who would govern the colony from England. Seventy-one men served as Trustees during the life of the Trust. Trustees were forbidden by the charter from holding office orland in Georgia, nor were they paid. Presumably, their motives for serving were humanitarian, and their motto was Non sibi sed aliis ("Not for self, but for others"). The charter provided that the body of Trustees elect fifteen members to serve as an executive committee called the Common Council, and specified a quorum of eight to transact business. As time went on, the council frequently lacked a quorum; those present

One face of the 1733 seal of the Georgia Trustees features two figures resting upon urns. They represent the Savannah and Altamaha rivers, which formed the northwestern and southeastern boundaries of the province.

Twelve Trustees attended the first meeting on July 20, 1732, at the Georgia office in the Old Palace Yard, conveniently close to Westminster. Committees were named to solicit contributions and interview applicants to the new colony. On November 17, 1732, seven Trustees bade farewell to Oglethorpe and the first settlers as they left from Gravesend aboard the Anne. The Trustees succeeded in obtaining £10,000 from the government in 1733 and lesser amounts in subsequent years. Georgia was the only American colony that depended on Parliament's annual subsidies.

The most active members of the Trust, in terms of their attendance at council, corporation, or committee meetings, were, in order of frequency, James Vernon, the earl of Egmont, Henry L'Apostre, Samuel Smith, Thomas Tower, John Laroche, Robert Hucks, Stephen Hales, James Oglethorpe, and Anthony Ashley Cooper, fourth earl of Shaftesbury. The number of meetings attended ranged from Vernon's 712 to Shaftesbury's 266. Sixty-one Trustees attended fewer meetings.

James Vernon, one of the original Associates of Dr. Bray and an architect of the charter, maintained an interest in Georgia throughout the life of the Trust. He arranged the Salzburger settlement and negotiated with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts for missionaries. He differed from Egmont and Oglethorpe in his willingness to respond to the colonists' complaints. When Oglethorpe became preoccupied with the Spanish war, Vernon proposed the plan of dividing the colony into two provinces, Savannah and Frederica, each with a president and magistrates. The Trustees named William Stephens president in Savannah, and he served until 1751, when he was replaced by Henry Parker in the final year of the Trust's tenure. Oglethorpe neglected to name a president for Frederica, and the magistrates there were instructed to report to Stephens. The Trustees did not want to appoint a single governor because the king in council had to approve the appointment of governors, and the Trustees preferred to keep control in their hands. After Egmont's retirement in 1742, Vernon became the indispensable man. He missed only 4 of 114 meetings during the last nine years of the Trust and supervised the removal of restrictions on land tenure, rum, and slavery.

Egmont, the first president of the Common Council and the dominant figure among the Trustees until his retirement, acted as Georgia's champion in Parliament. He strongly opposed Walpole's attempts to conciliate Spain at the expense of Georgia. He had to walk a careful line, however, because the Trustees depended upon Walpole for their annual subsidies.

Other Trustees contributed according to their abilities. Henry L'Apostre advised on finances, Samuel Smith on religion, and Thomas Tower on legal matters, particularly on instructions to Georgia officials. Stephen Hales's closeness to the royal family and his standing as a scientist lent prestige to the body of Trustees. Shaftesbury, a political opponent of Walpole, joined the Common Council in 1733 and, except for a brief resignation, remained faithful to the end. He led the negotiations to convert Georgia to a royal colony. For the entire twenty years the Trustees employed only two staff members, Benjamin Martyn as secretary and Harman Verelst as accountant.

Georgia Indians in London

Oglethorpe returned to England in June 1734 with goodwill ambassadors in the persons of Yamacraw chief Tomochichi, Senauki, his wife, their nephew Toonahowi,

As the principal mediator between the native population and the new English settlers during the first years of Georgia's settlement, Tomochichi (left) contributed much to the establishment of peaceful relations between the two groups and to the ultimate success of Georgia. His nephew, Toonahowi, is seated on the right in this engraving, circa 1734-35, by John Faber Jr.Tomochichi

and six other Lower Creek tribesmen.

The Indians were regarded as celebrities, feted by the Trustees, interviewed by the king and queen, entertained by the archbishop of Canterbury at Lambeth Palace, and made available to meet the public. All but two of them posed with a large number of Trustees at the Georgia office for the painter William Verelst. One of the absent Indians died of smallpox, despite the ministrations of the eminent physician Sir Hans Sloane, and was buried by his grieving comrades in the burial plot of St. John's in Westminster. After performing their social obligations, the Indians became tourists, visiting the Tower of London, St. Paul's Cathedral, Oglethorpe's Westbrook Manor, and Egmont's Charlton House, and enjoying a variety of plays, from Shakespearean dramas to comic farces.

Salzburgers, Moravians, and Highlanders

The Indians departed on October 31, 1734. With them went fifty-seven Salzburgers to join the forty-two families already in Georgia at Ebenezer. In 1734 and 1735 two groups of Moravians went to Georgia. As pacifists they opposed doing military duty and left Georgia by 1740. After delivering the Indians and Salzburgers to Georgia, Captain George Dunbar took his ship, the Prince of Wales, to Scotland. Dunbar and Hugh Mackay recruited 177 Highlanders, most of them members of Clan Chattan in Inverness-shire. In 1736 the Highlanders founded Darien on Georgia's southern boundary, the Altamaha. Dunbar subsequently served as Oglethorpe's aide in Georgia and in Oglethorpe's campaign against the Scots in 1745.

Oglethorpe went to Georgia in 1736, with the approval of his fellow Trustees, to found two new settlements on the frontiers, Frederica on St. Simons Island and Augusta at the headwaters of the Savannah River in Indian country. Both places were garrisoned by troops. In 1737 Oglethorpe returned to England to demand a regiment of regulars from a reluctant Walpole. Not only did he get his regiment and a commission as colonel, but Egmont persuaded Walpole to pay for all military expenses.

Trustee Legislation and Reactions

In 1735 the Trustees proposed three pieces of legislation to the Privy Council and had the satisfaction of securing the concurrence of king and council. An Indian act required Georgia licenses for trading west of the Savannah River. Another act banned the use of rum in Georgia. A third act outlawed slavery in Georgia. South Carolina protested the Indian act vehemently and objected to the Trustees' order to restrict the passage of rum on the Savannah River. The Board of Trade sided with South Carolina, and a compromise was reached, allowing traders with Carolina licenses to continue their traditional trade west of the Savannah River. The Trustees objected to the Board of Trade's tampering and refrained from proposing any additional legislation requiring approval of the Privy Council.

Continual complaints by the colonists and the near abandonment of Georgia during the war with Spain discouraged all but the most dedicated of the Trustees. Especially embarrassing was the list of grievances presented on the floor of Parliament by Thomas Stephens, son of the Trustees' agent in Georgia, William Stephens. A committee went through the motions of looking into the complaints and then exonerated the Trustees. Stephens was made to kneel in apology on the floor of Parliament. However, the prestige of the Trustees had been wounded, and their influence in Parliament weakened. Walpole lost office in 1742, and the new administration declined the Trustees' request for funding. Egmont resigned in protest, but not all the Trustees gave up. Under the leadership of Vernon and Shaftesbury, the Trustees conciliated the administration, and the government renewed the annual subsidies until 1751, when the Trustees' request was again denied.

Oglethorpe returned from Georgia in 1743 and never again showed the same enthusiasm for the work of the Trust. He disagreed with the relaxation of the ban on rum in 1742 and with the admission of slavery in 1750. He engaged in an unfortunate argument with the Trustees over expenses. The accountant claimed that he owed the Trust £1,412 of funds used for military purposes for which he had been compensated. Oglethorpe countered that the Trustees owed him far more than that amount. No agreement was reached. Oglethorpe attended his last meeting on March 16, 1749.

End of Trustee Rule

In March 1750 the Trustees called upon Georgians to elect delegates to the first representative assembly but cautioned them only to advise the Trustees, not to legislate. Augusta and Ebenezer each had two delegates, Savannah had four, and every other town and village had one. Frederica, now practically abandoned, sent no delegate. Sixteen representatives met in Savannah on January 14, 1751, and elected Francis Harris speaker. Most of the resolutions concerned improving trade. The delegates showed maturity in requesting the right to enact local legislation, and they opposed any annexation effort on the part of South Carolina. The Trustees intended to permit further assemblies, but the failure of Parliament to vote a subsidy in 1751 caused the Trustees to enter into negotiations to turn the colony over to the government a year before the charter expired. Only four members of the Trust attended the last meeting on June 23, 1752, and of the original Trustees only James Vernon persevered to the end.

An Introduction to JAMES EDWARD OGLETHORPE

by Mr. Scott White

Supported in Part By The Georgia Humanities Council And The National Endowment For The Humanities And Through Appropriations From The Georgia General Assembly.

James Edward Oglethorpe [the fifth son, the ninth child of Sir Theophilus and Lady Eleanor (Wall) Oglethorpe] was born at the family estate of Westbrook near the town of Godalming in the county of Surry, England on December 22, 1696. He was christened the following day in London at St. Martin-in-the-Fields by the Archbishop of Canterbury. His family were strong Jacobites (supporters of the dethroned James II) but James Edward Oglethorpe was never bound by this tradition. He was to be an individualist making his judgements on the basis of each issue and in some areas he was not only independent minded, he was far ahead of his time.

At an early age young James entered the British Army and saw active service in Flanders under the military genius of the age, the Duke of Marlborough. Later he volunteered as secretary and aide-de-camp to Prince Eugene of Savoy, fighting in the siege of Belgrade in Turkey and having his servant, that was next to him, killed in action. Young James also entered Eton College and Corpus Christi college, Oxford and eventually received his degree of A. M. in 1731. Following the tradition of father and brother, Oglethorpe was elected, in 1722, a member of the House of Commons from Haslemere and held this seat through seven Parliaments for thirty two years until his defeat in 1754. He again stood for election in 1768 but he was again defeated.

In his first five years in the House of Commons he was appointed to forty two Parliamentary committees dealing with a wide variety of subjects, including a 1724 "committee to consider a Bill for the relief of insolvent debtors.". He also became interested in the low rates of pay for the men of the Royal Navy, the mode of their payment and the terrible grievance of impressment. His concern culminated in his quasi-anonymous Sailor's Advocate, a fifty two page indictment of the conditions of the period. It was printed by H. Whitridge and sold for sixpence and was published in an eighth edition as late as 1828. Oglethorpe claimed that impressment jeopardized trade and liberty and this violated the Magna Carta and the Petition of Right.

Next Oglethorpe became involved in prison reform. His personal friend, Robert Castell, had published a handsome folio volume entitled Villas of the Ancients but his bankruptcy put him in the infamous Fleet Prison where he contracted smallpox and died. Believing that the prison warden was directly responsible for Castell's death, Oglethorpe, in 1729, was appointed chairman of a fourteen man committee "to inquire into the State of the Gaols of this Kingdom and report the same with their Opinion thereupon." Oglethorpe's committee made three reports to the Parliament, specifically charging the jailor as having "exercised an unwarrantable and arbitrary Power, not only in extorting exorbitant Fees, but oppressing Prisoners for Debt, by loading them with Irons, worse than if the Star-Chamber was still subsisting, and contrary to the great Contempt thereof, as well as of other good Laws of this Kingdom." Parliament granted limited relief by the passage of a Prison Reform Act of 1729 which released some on thousand debtors from jail but not until 1869 did Parliament effectively abolish imprisonment for debt in England.

Also, in 1729, Oglethorpe advocated a high tax on the consumption of gin and thereby encouraged the drinking of comparatively innocuous malt liquors. In the personal life he drank beer and wine moderately while abstaining from hard liquors. In Georgia he prohibited all hard liquors but permitted wine, beer and ale. In 1732 he stressed the importance of discovering colonial opinion on a proposed imperial sugar tax: "We ought to have no regard to the particular interest of any country or set of people; the good of the whole is what we ought only to have under consideration; our colonies are all a part of our own dominions; the people in every one of them are our own people, and we ought to show an equal respect to all."

Like many statesmen of today, Oglethorpe was concerned with the twin problems of poverty and unemployment. His solution would be the founding of Georgia. As his friend the Earl of Egmont wrote in his diary of February 13, 1730: "The scheme is to procure a quantity of acres either from the Government or by gift or purchase in the West Indies (by that he meant the New World) and to plant thereon a hundred miserable wretches who being let out of gaol by last years's Act, are now starving about the town for want of employment; and that they should be settled all together by way of colony, and be subject to subordinate rulers, who should inspect their behavior and labour under one chief head; that in time they with their families would increase so fast as to become a security and defense of our possessions against the French and Indians of those parts; They should be employed in cultivating flax and hemp, which being allowed to make into yearn would be returned to England and Ireland and greatly promote our manufactures."

In 1730 Oglethrope formed the Georgia Society, composed largely of the members of the Parliamentary jail committee. Later that year the Georgia Society petitioned the Privy Council stating "that the cities of London, Westminister, and parts adjacent, do abound with great numbers of indigent persons, who are reduced to such necessity as to become burthensome to the public, and who could be willing to seek a livelihood in any of his majesty's plantations in America, if they were provided with passage, and means of settling there." For his part Egmont wrote in his diary: "There is a project on foot for settling a colony of a hundred English families on the river Savannah that bounds the North (he meant South) side of Carolina, by which it is proposed that a vast tract of good land uncultivated by reason of the incursion of the Indians will be protected and of course improved to the enriching that province, and to the great advantage of England. The King is to give the land, and the charges furnished by subscriptions, and 5 or 6000 is all we think necessary to beginning it. This being entirely calculated for a secular interest meets with approbation, and the Board of Trade have agreed with the undertakers upon a favorable report to be made of it to His Majesty, who, with the Ministry, and the merchants of the city, commend the design. Mr. Oglethorpe, a young gentleman of very public spirit and chairman of the late committee of gaols, gave the first hint of this project last year and has very diligently pursued it. Several Parliament men, clergy, &c. are commissioners for executing it, myself among others. Is is proposed the families there settled shall plant hemp and flax to be sent unmanufactured to England, whereby in time much ready money will be saved in this Kingdom, which now goes out to other countries for the purchase of these goods, and they will also be able to supply us with a great deal of good timber. 'Tis possible too they may raise white mulberry trees and send us good raw silk. but at the worst they will be able to live there, and defend that country from the insult of their neighbors, and London will be eased of maintaining a number of families which being let out of gaol have at present no visible way to subsist."

Oglethorpe expanded the original plan and in 1731 explained that the promoters had "resolved not . . . to confine this charity to prisoners, but extend it as far as their funds would allow to all poor families as would be desirous of it. And in case it would not extend to all, to choose out from among the prisoners and others, such as were most distressed, virtuous and industrious." Oglethorpe added that "the undertaking hath met with great encouragement, as well from public as from private persons; the former being sensible that to this they will owe the preservation of their people, the increasing the consumption of their manufactures, and the strengthening their American dominion. Mankind will be obliged to it, for the enlarging civility, cultivating wild countries and founding of colonies, the posterity of which may in all probability be powerful and learned nations. And lastly Christianity may be benefited."

In 1732 after much red tape King George II issued a royal charter to a corporation of 21 persons to be called "the Trustees for establishing the Colony of Georgia in America." The charter was good for 21 years, after which time Georgia was to become a royal colony. To insure the charitable aims of the corporation , no trustee could receive any salary nor could any trustee hold any land in Georgia. Later when the Trustees designed the seal it carried with it a Latin inscription "Non sibi, sod aliis" (Not for themselves but others). Of all the proprietary colonies Georgia was unique in this respect. Other colonies existed for the benefit of their owners. As trustee Oglethorpe never asked for nor received a pound, shilling or pence for his service to the colony.

By the royal charter of 1732 George II granted the Trustees a vast tract of land between the mouths of the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers and from their sources westward to the South Seas or as we now call it the Pacific Ocean. It was a vast grant so much so that even today Georgia is the largest state east of the Mississippi River. The charter promised all colonists all rights of English (as if they had never left England) including a freedom of worship. The only exception was a prohibition on public worship be Roman Catholics. It was an old fear that religion might pull men's allegiances towards the Spaniards in St. Augustine. The charter also limited land ownership by anyone to 500 acres. Georgia was to be different from Carolina where a few persons owned much land and most persons owned little or on land. Georgia was to be a land of poor but honest folks.

To promote positive propaganda Oglethorpe wrote A New and Accurate Account of the Provinces of South Carolina and Georgia which was published in 1732. Also in that year Oglethorpe's mother died and this left him free to take personal direction of the enterprise. Before sailing Oglethorpe attended 17 meeting of the Trustees only being absent on two occasions. In all 114 charter colonists were selected and brought over on the Ship Ann, 200 tons burden, commanded by Captain John Thomas and owned by Samuel Wragg, merchant. Ample food and drink were provided. Four days of each week the passengers ate beef, two days they had pork and one day they had fish. The water allowance was one quart per day "whilst the beer lasted, and two quarts per day after the beer was done." The ship sailed November 17, 1732, arrived at Charles Town in South Carolina on January 13, 1733, then on to Beaufort arriving on January 20. While the colonists waited there Oglethorpe and Lieutenant Colonel William Bull of South Carolina selected the site for the town of Savannah. Finally a sloop and five small boats brought the colonists to the site on February 1, 1733 (February 12, 1733 N.).

After a year in Georgia Oglethorpe returned to England in 1734 with the chief of the Yamacraw Indians Tomochichi, with his wife Scenawki, his nephew and adopted son Toonahowi and six other important chieftains. The Indians were wined and dined at great expense. They were received by King George II and also the Archbishop of Canterbury. Scenawki was fitted out with a glass eye and from all reports greatly improved her personal appearances. Tomochichi was greatly impressed with the English and on one occasion expressed his surprise that such short-lived men should build such long-lived houses. Treaties of peace and friendship were signed with the English before the Indians returned to Georgia.

Oglethorpe returned to Georgia staying one year and then returned to England in 1736 to raise funds for the colony of Georgia. The Spanish government demanded that Oglethorpe not be allowed to return to Georgia but the English government allowed him to return to Georgia with a volunteer regiment of over 600 men. Upon his arrival Oglethorpe saw war clouds on the horizon. Accordingly in 1740 he had an expedition into Spanish florida. He captured the town of St. Augustine but was unable to take the Castilllo San Marcos. In 1742 the Spanish retaliated by invading Georgia but they were stopped by Oglethrope's men at the so called Battle of Bloody Marshon St. Simon's Island. Georgia was safe. George Whitefield (the founder of Bethesda Orphanage) wrote: "The deliverance of Georgia from the Spaniards is such as cannot be paralleled but by some instances out of the Old Testament." Oglethorpe was rewarded with this promotion to the rank of Brigadier General on February 13, 1743. Hitherto the title of General which had been accorded him was purely honorary and conventional. After ten years in Georgia Oglethorpe left for England on July 22, 1743. He was never to return again.

In England he had to face 19 charges made by a Lieutenant Colonel William Cook before a Court Martial with the Rt. Hon. Lord Mark Korr, President. Their findings: "We do find that not anyone Article thereof is made out, and that every one of them is either frivolous, vexatious, or malicious, and without foundation. We, therefore, are most humbly of the opinion that the said Lt.. Colonel William Cook deserves to be dismiss'd from Your Majesty's service." Oglethorpe was completely vindicated(55).

A few months later on September 15, 1744, in the King Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey, Oglethorpe married Lady Elizabeth Wright, the only daughter of Sir Nathan Wright, Baronet and heiress of Cranham Hall in the village of Cranham, Essex County, England about sixteen miles from London. The Oglethorpes honeymooned at Westbrook which he had inherited in 1732. After Oglethorpe's death it was sold and eventually it was purchased by the Countess of Meath who turned it in 1892 into a Home of Comfort for Epileptics for Women and Children. The Oglethorpes also acquired a London townhouse in which they generally spent the winter season but this was later torn down. Cranham Hall became the summer residence of the Oglethorpes for forth years of their married life. Afterwards the estate descended to the Marquis de Bellegrade, the grandson of one of Oglethorpe's sisters. Today it still survives as a private residence.

In 1745 Oglethorpe was promoted to Major General but the Jacobite insurrection of that year nearly destroyed his reputation. Ordered to pursue the defeated rebels Oglethorpe was later accused by the Duke of Cumberland of "having disobeyed or neglected his orders and suffered the Rear of the Rebells near Shap to escape." Once again Oglethorpe faced a Court Marital this time with Lieutenant General Thomas Wentworth as President. Their findings: "We are of Opinion that Major General Oglethorpe is not guilty of the crime laid to his charge and do, therefore, acquitt him of the same." In 1747 Oglethorpe was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and in 1765 he was appointed General. Within a short time he became the senior general for the entire British Army. In 1818 H. McCall's History of Georgia claimed that at the outbreak of the American Revolution, Oglethorpe was offered field command of the British forces in America. The story has been repeated many times by otherwise respectable historians but the story is not supported in the British War Office records. Besides his extreme age (80) would have ruled out such an offer if not Oglethorpe's kindly view of colonial affairs.

Oglethorpe spent the last year of his life in the famous literary circle which included such notables as Dr. Johnson, Boswell, Wapole, Goldsmith, Burke and others. Boswell has it that once when dining at his home Johnson pressed Oglethorpe to "give the world his life. I know no man whose Life would be more interesting. It I were furnished with materials, I should be very glad to write it." Unfortunately no biography was forthcoming. The great artist Sir Joshua Reynolds painted a portrait of Oglethorpe but it was unfortunately destroyed in a fire.

In 1784 the young Hannah Moore wrote of her encounter with Oglethorpe: "I have got a new admirer. We flirt together prodigiously; it is the famous General Oglethorpe, perhaps the most remarkable man of his time. . . the finest figure you ever saw. He perfectly realizes all my ideas of Nestor. His literature is great, his knowledge of the world extensive, and his faculties as bright as ever; he is one of the three persons still living who were mentioned by Pope. . . He was the intimate friend of Southern, the tragic poet, and of all the wits of that time. His is perhaps the oldest man of a gentleman living. . . He is quite a preux chevalier, heroic, romantic, and full of the old gallantry."

In 1785 Oglethorpe attended the four day sale of Dr. Johnson's library at Christie's. As Samuel Rogers recalled, "at the sale of Dr. Johnson's books, I met General Oglethorpe, thin very, very old, the flesh of his face looking like parchment. He amused us youngsters by talking of the alterations that had been made n London and of the great additions it had received within his recollections." The only well known portrait of Oglethorpe was made by Samuel Ireland at the Johnson book sale. It is the portrait of an ancient person. Oglethrope is lean as a grasshopper. As Austin Dobson has it: "He wears a military-looking hat, and a caped coat with deep cuffs and ruffles. His sword hilt projects between his skirts; and in his right hand, which is propped upon a stout walking-cane, he holds a book which has been knowked down to him, and which he is reading attentively without the aid of spectacles."

Also in 1785 Horace Walpole wrote that Oglethorpe "has the activity of youth when compared to me. His eyes, ears, articulation, limbs, and memory would suit a boy, if a boy could recollect a century backwards. his teeth are gone; he is a shadow, and a wrinkled one; but his spirits and his spirit are in full bloom." On June 1, 1785 John Adams was received by King George III as the first minister to the Court of St. James's from the United States of America. Three days later Oglethorpe visited Adams and expressed "a great esteem and regard for America, much regret at the misunderstanding between the two countries, and was very happy to have lived to see the termination of it." Quite appropriately Adams returned Oglethorpe's visit. At last on June 30, 1785 Oglethorpe died not as one might suppose, of old age at 89, but of a violent fever which would have killed him at any age. He was buried across the lawn from Cranham Hall at All Saints Church where his wife was to join him two years later. Oglethorpe was a great man and recognized as such by his own time. Little more can be said that that his presence on this earth made it "a bit more beautiful and better."

Since Oglethorpe helped establish the colony of Georgia, he has been honored and remembered in many different ways. In 1737, Gentleman's Magazine sponsored a contest for the best poem entitled "The Christian Hero". The first prize was a gold medal with a the head of James Oglethorpe on one side. The United States post office has twice honored Oglethorpe with a stamp bearing his image. The first occasion was to mark the bicentennial of Georgia. In 1933 it issued a 3 cent stamp in his honor. The second occasion was to commemorate the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Georgia. A 13 cent stamp was issued in 1983 to honor Georgia's founder.

Georgia has both a county and town named for Oglethorpe. Oglethorpe County was established in 1793. Oglethorpe County is bordered by Greene, Madison, Elbert and Wilkes Counties. The town of Oglethorpe is located in the Macon County. Oglethorpe, located on the west side of the Flint River, was laid out in 1830. It became the county seat in 1854. Oglethorpe became a regular stopping place for the stage coach and eventually the railroad. Thousands of wagons began to haul cotton in Oglethorpe and the population grew to 20 thousand. A smallpox epidemic swept through and many died, houses were burned and the town never recovered.

Oglethorpe University was established in 1835. Originally called Oglethorpe College, it was built at Midway about 2 miles from Georgia's former capital of Milledgeville. It was built under the auspices of the Presbyterian Church and was referred to Old Midway Seminary. After the War Between the States, the University was removed to Atlanta where it closed in 1872. It was re-established in 1913 under the leadership of Rev. (Dr.) Thornwell Jacobs a Presbyterian minister. The cornerstone of the new administration was laid in 1915.

The city fathers of Savannah were desirous of having an army barracks located within the city. In 1823 they petitioned the Secretary of War to build a barracks and offered to purchase the land for the undertaking. The U. S. government to furnish the materials and use soldiers to perform the labor required. Oglethorpe Barracks was completed in 1834 on the site where the Desoto Hilton now stands. The site was never occupied by U. S. troops. In 1852 the city proposed to purchase the site back from the U. S. government and in 1853 the government honored that wish. Oglethorpe Barracks was used by local military volunteer companies of Savannah until 1864, when Savannah was captured by Union troops. The barracks were sold to the Savannah Hotel Corporation for $75,000 in 1879. The barracks were torn down in the 1870s to make room for the Desoto Hotel. Construction on the Desoto Hotel began in 1888 and was completed in 1890. The hotel had 5 stories, 206 rooms, a solarium, barber shop, drug store and restaurant.

Within the city of Savannah there have been many other things named in Oglethorpe's honor: Oglethorpe Club, Oglethorpe Square, Oglethorpe Ward, Oglethorpe Street, Oglethorpe Bench and the Oglethorpe Monument. Two institutions which no longer exist are the Oglethorpe Savings and Trust and the Oglethorpe Insurance Company. Also, on the outskirts of Savannah on Wilmington Island, is a Hotel previously called the Oglethorpe Hotel that is now known as the Savannah Sheraton.

The Oglethorpe Club was established in 1875. Its members were some of the leading citizens of the city. The club was located at the corner of Bull and Broughton on the second of the Odd Fellows hall which was another men's club. The Oglethorpe is now located the Molyneux house, the former residence of General Henry R. Jackson, at the corner of Bull and Gaston streets.

Oglethorpe Square was laid out in 1733. It is the second square south of Bay street on Abercorn and is bounded on the north and south by State and York streets. Oglethorpe Ward was established in 1787 along West Broad (now Martin Luther King Boulevard) Street.

Oglethorpe Avenue, one of the original streets in Oglethorpe's plan for the city, has not always gone by that name. It was originally called South Broad Street and marked the edge of the city for many years. One former resident remembers that many local residents often referred to it as "Under the Trees" street because it was a long shady avenue of Pride of India trees that spanned the width of the city from East Broad to West Broad. "Under the Trees" was the usual route taken by funeral processions on the way to the Old Cemetery at the corner of South Broad and Abercorn. South Broad was later renamed Oglethorpe Avenue.

In 1906, the Georgia General Assembly appropriated $15,000 for a monument to commemorate the founder of Georgia. Chippewa Square was designated as the site because it was owned by the State. Daniel Chester French was chosen as the sculptor and Henry Bacon designed by base. The unveiling of the monument was on November 23, 1910. Many dignitaries and military units participated in a parade through the city ending in a ceremony in the square. Dignitaries in attendance included the Honorable Joseph M. Brown, Governor of Georgia, the British Ambassador and the Resident British Consul. Bacon and French went on to produce the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

THE CHIPPEWA

Wiki:

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, or Chippewa are an "Anishinaabeg" (see below) group of indigenous peoples in North America. They live in Canada and the United States and are one of the largest Indigenous ethnic groups north of the Rio Grande. In Canada, they are the second-largest First Nations population, surpassed only by the Cree. In the United States, they have the fourth-largest population among Native American tribes, surpassed only by the Navajo, Cherokee, and Lakota-Dakota-Nakota peoples. The Ojibwe people traditionally have spoken the Ojibwe language, a branch of the Algonquian language family. They are part of the Council of Three Fires and the Anishinaabeg, which include the Algonquin, Nipissing, Oji-Cree, Odawa and the Potawatomi. The majority of the Ojibwe people live in Canada. There are 77,940 mainline Ojibwe; 76,760 Saulteaux and 8,770 Mississaugas, organized in 125 bands, and living from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia. As of 2010, Ojibwe in the US census population is 170,742.

Because General Oglethorpe had no monument the Georgia Society and the Colonial Dames of America petitioned the city engineer, using old maps, to locate the exact spot where General Oglethorpe, founder of the colony, pitched his tent and rested on the first night he spent in Georgia. In 1905 they ordered the design and construction of a curved granite bench to be placed on that site. That site is near the intersection of Bay and Whitaker.

The road to Tybee was opened to automobiles in 1925. This event paved the way to the rapid settlement of the islands it crossed. The Abbott Hotels Corporation opened the Oglethorpe Hotel, often referred to by the locals as the General Oglethorpe Hotel, in 1925. The hotel was located on Wilmington Island overlooking the Wilmington River. It still stands today but is called the Savannah Sheraton.

Nestled near Chattanooga Tennessee, Lookout Mountain, and Chickamauga National Military Park was Fort Oglethorpe. Fort Oglethorpe was used as an army induction center during World War I and World War II. It was completed in 1904 and was primarily a cavalry post. It also was used for the Women's Army Corps and to house German prisoners of war during World War II. The fort was disbanded in 1947, declared surplus and sold off in parcels in 1948. Today Fort Oglethorpe is private property. The remnants of the fort and others buildings were incorporated as a city in 1949. Today the town of Fort Oglethorpe has about 100 building and a population of about 5,000.

The Oglethorpe Hotel opened on January 9, 1888 in Brunswick, Ga. It was a magnificent structure. Visitors and members to the famous Jekyll Island Club would often arrive by train and spend the night at the Oglethorpe before being ferried to Jekyll the next day. The hotel was designed by J. A. Wood and was built on the site of the Oglethorpe House, built in 1837 and accidentally burned during the War Between the States. The Oglethorpe Hotel was the winter hotel and the St. Simons Hotel, owned by the same corporation, was the summer hotel. The Oglethorpe Hotel had its own dock on the Brunswick river. The Oglethorpe was constructed using 3 million brick. It had 107 rooms, electric lighting, was 4 stories and cost one quarter million dollars to construct in 1888. It was noted for its tear drop Victorian architecture and gingerbread design. It also had a two story rotunda and marble dinning room floors. The ballroom was the center of Brunswick social life with its live orchestra. The Oglethorpe Hotel was torn down in 1958 to make room for a department store and a Holiday Inn.

For more on Black PaleoAmericans and Native Americans please visit these pages:

Prehistoric Americans

Ancient North Americans

The Australians and Polynesians

|

| Click for Realhistoryww Home Page |